What you’ll learn:

- HbA1c reflects your average blood sugar over several months, showing patterns that are linked to your risk of heart disease, cognitive decline, and aging.

- Research shows that HbA1c is a powerful marker of metabolic health, offering insight into how your body may age in the years ahead.

- Even in people without diabetes, higher HbA1c levels have been linked to increased risk for certain conditions, making it a meaningful signal for long-term health.

- Testing and tracking your HbA1c over time can show whether your habits or treatments are supporting steadier blood sugar.

Most people want to feel good today and stay healthy for years to come. That means having steady energy throughout the day, thinking clearly, sleeping well, and moving through life without fatigue or brain fog. Those day-to-day experiences are often shaped by something happening quietly in the background: how your body manages blood sugar over time.

When blood sugar patterns stay relatively stable, many people notice they feel better: more consistent energy, fewer crashes, better focus. When those patterns are less stable, with larger fluctuations in blood sugar levels, people may experience afternoon slumps, irritability, trouble concentrating, or feeling worn down for no apparent reason.

Hemoglobin A1c, often called HbA1c or A1c, captures those patterns through a simple blood test. It reflects your average blood sugar over the past two to three months by measuring how much glucose has attached to red blood cells, giving a reliable snapshot of long-term blood sugar patterns.

HbA1c is most commonly known as a tool for diagnosing and monitoring diabetes, helping doctors see how well someone is managing their blood sugar over time. But here’s what many people don’t realize: this number matters even if you don’t have diabetes.

Higher HbA1c levels have been linked in studies to a greater risk of heart disease, cognitive decline, and earlier death, even among people without diabetes.

But beyond those long-term risks, elevated blood sugar patterns can also affect how you feel right now—contributing to fatigue, brain fog, mood swings, and that sluggish feeling that makes it harder to get through the day.

Understanding HbA1c can help you connect everyday habits to how you feel today, as well as your long-term health and longevity. Let’s take a closer look at why this marker matters and how it fits into healthy aging.

What is HbA1c?

Think of HbA1c as a report card for how your body has been handling blood sugar over the past few months. It’s not a snapshot of one moment; it’s more like an average that shows the bigger picture of what’s been going on with your glucose levels over the previous two to three months.

When your HbA1c number starts creeping up, it’s usually a sign that sugar has been hanging around in your bloodstream longer than your body can easily handle. That matters for your metabolic health, both now and down the road.

Physiologically, hemoglobin A1c forms when glucose binds to red blood cells as they circulate through the body. Because red blood cells live for about 120 days, the percentage of sugar attached to them mirrors blood sugar patterns during that period.

HbA1c vs. glucose readings: What’s the difference?

A regular glucose reading, like what you’d get from a finger prick or continuous glucose monitor, tells you what your blood sugar is doing right now, at that moment. It’s helpful for seeing how your body responds to a specific meal, workout, or stressful day.

HbA1c, on the other hand, zooms out. It shows the average of all those daily ups and downs over months. You might have a normal glucose reading one morning but still have an elevated HbA1c if your blood sugar has been running high most of the time. That’s why HbA1c is useful for understanding longer-term patterns and risks, while daily glucose readings help you adjust habits in real time. Ideally, tracking both gives you the most complete picture.

HbA1c: What can it tell you about your health today and long-term

Keeping an eye on your HbA1c matters because it tells a bigger story than a single blood sugar reading ever could. HbA1c reflects your average blood sugar over the past two to three months, which means it shows how often your body is dealing with elevated glucose—not just on a “bad day,” but as a pattern. When that number runs high, it usually means your system is under more metabolic strain.

Over time, that extra stress is linked to how you feel day to day and to long-term issues like heart and blood vessel disease, brain health changes, and even overall lifespan. Studies of people with type 1 diabetes show that higher HbA1c levels are more likely to experience fatigue, brain fog, increased inflammation, and insulin resistance. Research shows higher HbA1c levels can also contribute to problems like cardiovascular disease, stroke risk, cognitive decline, and frailty.

That’s why HbA1c is often described as a risk signal—while research continues to examine whether it directly drives certain health issues, its consistent links across studies make it a useful indicator of long-term health patterns.

Research has associated hemoglobin A1c levels with:

Short-term health

HbA1c doesn’t just matter for the future—it can make a noticeable difference in how you feel right now. HbA1c levels can reflect fluctuations that are associated with steady energy, better focus, and less intense hunger swings. Studies suggest a link between lowering HbA1c and improvements in daily symptoms like fatigue and mood, as well as better short-term metabolic health overall.

Even modest reductions in HbA1c have been associated in studies with fewer day-to-day symptoms tied to blood sugar spikes and dips.

In other words, getting HbA1c into a healthier range isn’t just about preventing problems years down the line—it can help your body feel more balanced, resilient, and comfortable today.

Lifespan and mortality risk

Large studies have found that mortality risk tends to rise when HbA1c climbs above certain levels. In a study, people without diabetes had a higher all-cause mortality rate when HbA1c was above 6%.

For people with diabetes, that higher risk often shows up above about 9%, while for people without diabetes, it appears above roughly 6%. Interestingly, very low HbA1c levels have also been linked to a higher risk, especially below 6% in people with diabetes and below 5% in those without.

Heart and vascular health

Long-term blood sugar levels matter for the heart and blood vessels. When HbA1c rises above about 7% in people with diabetes, or above about 6% in those without diabetes, studies have found a higher risk of cardiovascular-related death, including from heart disease and stroke. That’s because chronically elevated glucose can damage blood vessel walls, promote inflammation, worsen arterial stiffness, and increase plaque buildup, making it harder for your heart to pump and your blood to flow smoothly. In other words, those percent cut-offs aren’t arbitrary: they signal levels where the body’s systems are working harder and less efficiently, and that higher workload shows up as more cardiovascular events and deaths in long-term studies.

Brain health

Studies show that higher long-term blood sugar levels may affect how the brain ages. Higher HbA1c has been linked to faster aging of white matter, the tissue that helps signals travel efficiently in the brain. The effect translated to about half a year of additional brain aging per standard HbA1c increase (6.8 mmol/mol), with the strongest effects seen in men ages 60 to 73, including those without known diabetes. You can think of white matter like the brain’s wiring system—it helps different areas “talk” to each other quickly and clearly. When blood sugar stays elevated over time, that wiring can start to wear down sooner than it should, partly because high glucose increases inflammation and damages small blood vessels that feed the brain. As white matter health declines, people may notice slower processing speed, more trouble focusing, or feeling mentally foggy.

Frailty

Frailty isn’t just “getting older,” it describes a state where the body has less reserve and bounces back more slowly from stress. People who are frail may feel weaker, tire more easily, walk more slowly, lose muscle, or have a harder time recovering from illness, surgery, or even a minor fall.

HbA1c is linked to frailty because long-term high blood sugar puts constant stress on the body. Over time, it can contribute to muscle loss, inflammation, nerve damage, and problems with circulation—all of which make it harder to stay strong and stable.

Studies show that higher blood sugar can also interfere with how muscles use energy, which may leave people feeling fatigued and physically vulnerable. In short, when HbA1c stays elevated, the body has to work harder just to function, and that can accelerate the slide toward frailty as we age.

How HbA1c is measured and tested

HbA1c is checked with a blood test, usually done as part of routine lab work. You don’t need to fast beforehand.

Labs use standardized testing methods to see how much glucose has attached to hemoglobin inside red blood cells. These methods are carefully calibrated, and international standards help make sure results are consistent and comparable, no matter where the test is done.

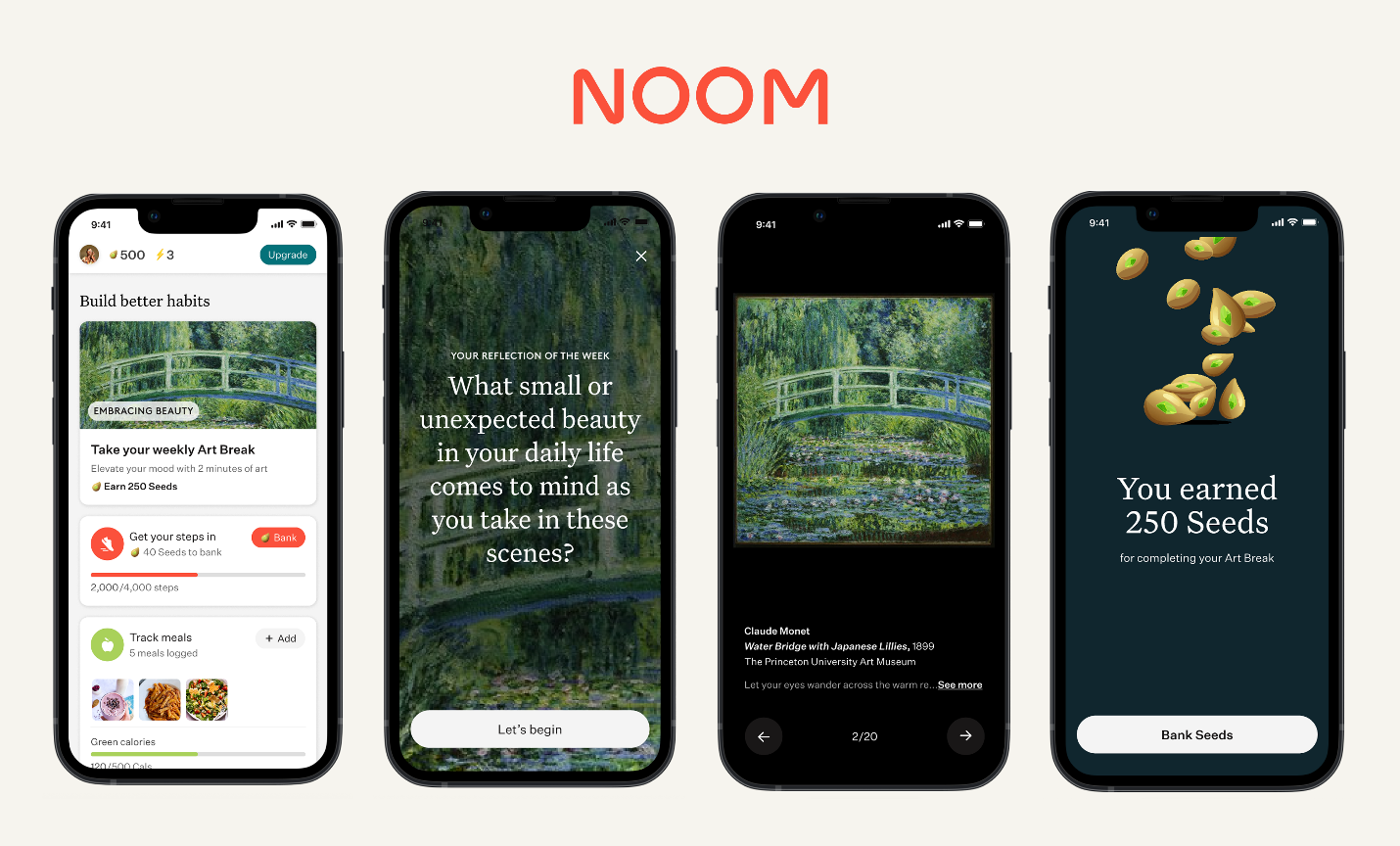

For people who prefer not to schedule lab or clinic visits, Noom Proactive Health Microdose GLP-1Rx Program offers a way to track HbA1c from home alongside other health markers.

Learn more: Inside Noom’s Proactive Health Microdose GLP-1Rx Program: Understanding the biomarkers

What affects HbA1c accuracy and reliability

HbA1c is generally a reliable way to reflect average blood sugar over the past two to three months. Small variations can happen, though, and results may be affected by things like recent illness, pregnancy, conditions that affect red blood cells, or certain medications. Short-term changes in diet, exercise, or stress right before the test usually do not make much difference.

Who should consider HbA1c testing?

This test is often recommended for people managing diabetes, people with elevated blood sugar, and adults during regular health screenings. The timing and frequency depend on overall health and clinical recommendations.

How HbA1c is calculated

HbA1c is measured directly in the lab as a percentage. That number reflects how much glucose has attached to hemoglobin in your red blood cells.

There are standard formulas used to convert HbA1c into an estimated average glucose (eAG) value, which helps translate the result into more familiar daily blood sugar terms. HbA1c is helpful, but it’s kind of abstract—it’s a percentage, not something most people see day to day. Estimated average glucose translates that percentage into an average blood sugar number (in mg/dL) that looks more like the readings you’d see on a glucose meter or continuous glucose monitor. That’s valuable because it helps you connect the dots between your daily habits and your lab results.

The most commonly used formula is:

- eAG (mg/dL) = (28.7 × HbA1c) − 46.7

You can also use a reliable online calculator to make the computation easier, such as the one provided by the American Diabetes Association.

HbA1c: Understanding your results

An HbA1c result is just a number until you understand what it indicates. Understanding your HbA1c results helps you see the bigger picture of how your blood sugar has been running over the last two to three months, not just on any single day. It’s a useful snapshot of how well your body is handling glucose overall.

In general, an HbA1c below about 5.7% is considered typical, 5.7% to 6.4% suggests prediabetes, and 6.5% or higher is in the diabetes range, though personal targets can vary. The most important thing to know is that HbA1c is about patterns: it shows trends over time and can help you understand whether what you’re doing is working or if adjustments might help.

Below is a simple way HbA1c values are usually categorized and interpreted:

| HbA1c range | Category | What it means |

|---|---|---|

| 5.0–5.5% | Goal or optimal target | Many clinicians aim for this range in healthy people, since lower values within the normal range are linked with better long-term health when blood sugar is stable. |

| Below 5.7% | Population reference range | Widely considered normal, but not necessarily optimal |

| 5.7–6.4% | Prediabetes range | Signals elevated blood sugar and a higher long-term risk |

| 6.5% or higher | Diabetes diagnostic threshold | Standard threshold used for diabetes diagnosis |

HbA1c: What affects the number?

HbA1c reflects patterns that build up over weeks, but there are still short-term factors that can play a role. Let’s take a look at some of the short-term factors that can influence HbA1c levels:

Short-term influences on HbA1c

- Infections or illness: Infections or illness can nudge HbA1c upward if they happen often or last long enough. When you’re sick, your body releases stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline to help fight the illness. Those hormones also signal the liver to release more glucose into the bloodstream. Research on infections like COVID-19 shows that sustained illness and inflammation can raise average blood sugar levels over weeks to months, which may show up as a higher HbA1c.

- Dehydration: Dehydration can indirectly contribute to a higher HbA1c by making glucose levels run higher more often. When you’re dehydrated, blood becomes more concentrated, which can raise glucose readings. Research has linked repeated low fluid intake with higher fasting glucose and higher HbA1c, especially in people with insulin resistance or diabetes. Occasional dehydration won’t move HbA1c much, but repeated patterns can.

- Alcohol intake: Alcohol intake can influence HbA1c through its effects on the liver, sleep, and glucose regulation. The liver plays a key role in managing blood sugar, and alcohol temporarily shifts the liver’s focus away from glucose control. Studies show alcohol can cause blood sugar swings—sometimes lower at first, then higher later—especially when it disrupts sleep. Over time, these repeated fluctuations can raise average glucose and HbA1c.

- Menstrual cycle: The menstrual cycle can affect HbA1c if glucose runs higher for several days each cycle. Hormonal changes—especially higher progesterone in the second half of the cycle—can reduce insulin sensitivity. Research has shown that many females experience higher blood sugar and increased cravings during this phase. While one cycle won’t change HbA1c, studies of people with type 1 diabetes suggest that there could be a link between cycle irregularities and higher HbA1c. (Note: these results may not be generalizable to women without diabetes or to adult populations.)

Long-term factors that influence HbA1c

- Higher body fat levels: Extra body fat can make it harder for insulin to do its job. When fat tissue—especially visceral fat around the abdomen—builds up, it releases inflammatory signals that reduce insulin sensitivity. That means glucose stays in the bloodstream longer instead of moving efficiently into cells. Large population studies consistently show higher HbA1c levels in people with higher body fat, even when they don’t have diagnosed diabetes. Over time, this chronic insulin resistance pushes average blood sugar up and shows up as a higher HbA1c.

- Thyroid conditions: Thyroid hormones play a quiet but powerful role in glucose balance. Both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism can affect HbA1c, but in different ways. Low thyroid hormone levels can slow metabolism and reduce glucose uptake by muscles, sometimes leading to higher blood sugar. High thyroid hormone levels can increase glucose production by the liver and raise insulin resistance. Studies have found that untreated thyroid disorders are associated with higher HbA1c levels, and that HbA1c often improves once thyroid function is brought back into range.

- Kidney or liver disease: These organs are central to how your body manages glucose over time. The liver helps store and release glucose between meals, while the kidneys filter glucose from the blood and help regulate insulin clearance. Chronic liver disease can increase insulin resistance and raise fasting glucose, while kidney disease can alter glucose handling and insulin metabolism in complex ways. Research shows that people with chronic kidney disease or liver disease often have higher HbA1c levels—or HbA1c that reflects ongoing metabolic stress—even when day-to-day glucose readings seem stable.

- Certain medications: Some drugs consistently shift blood sugar up or down over time.

- Long-term steroid use is well known to raise blood sugar by increasing insulin resistance and liver glucose output, and studies link steroid treatment to higher HbA1c.

- Some studies in psychiatric populations have observed higher or rising HbA1c levels among people treated with antipsychotics, compared with other psychotropic medications.

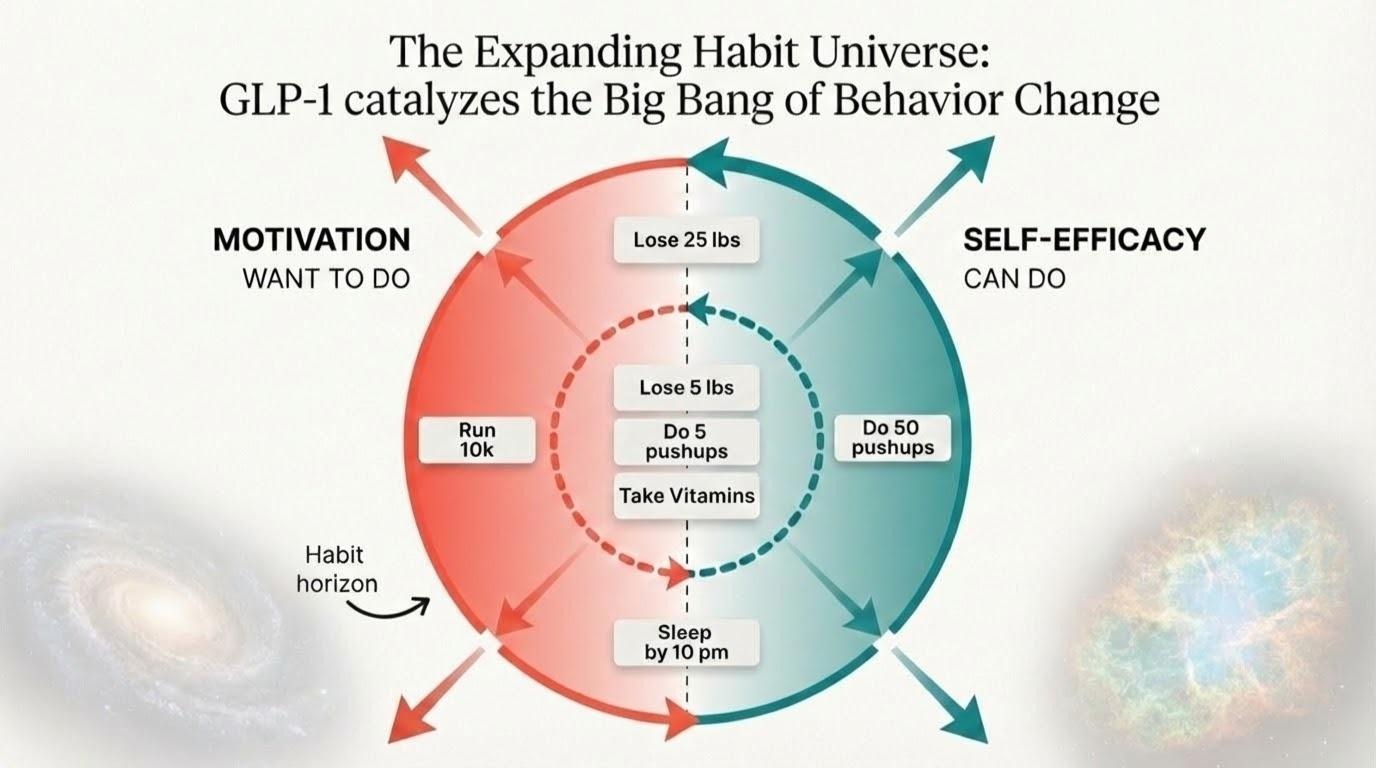

- Studies show that medications like metformin, GLP-1 receptor agonists, SGLT2 inhibitors, and DPP-4 inhibitors tend to lower HbA1c by improving insulin sensitivity, reducing glucose production, slowing digestion, or increasing glucose excretion. Large clinical trials consistently show measurable HbA1c changes—up or down—depending on the medication and how long it’s used.

Demographics and biology

- Aging: As we age, the body often becomes less responsive to insulin. Muscle mass tends to decline, while fat mass (especially visceral fat) increases, which can reduce insulin sensitivity and slowly push average blood sugar higher. Large studies show that HbA1c levels tend to rise with age, even in people without diabetes, reflecting these gradual metabolic shifts.

- Sex-related hormone patterns: Hormones like estrogen and testosterone influence how the body handles glucose. Estrogen helps support insulin sensitivity, which is why HbA1c can rise after menopause, while lower testosterone in men has also been linked to higher insulin resistance. Research has found measurable differences in HbA1c across hormonal transitions (such as menopause or androgen decline), even when fasting glucose looks similar.

- Ethnicity-related differences: Studies consistently show differences in HbA1c across racial and ethnic groups. Research suggests this may reflect a mix of factors, including genetics, red blood cell lifespan, insulin sensitivity, and social or environmental stressors—meaning HbA1c doesn’t always tell the exact same story for everyone.

- Genetics: Research shows that genes influence both glucose handling and how HbA1c is formed. Some people are genetically predisposed to insulin resistance or higher glucose production, while others have differences in red blood cell turnover that can raise or lower HbA1c independently of true blood sugar levels. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified multiple genetic variants linked to HbA1c, showing that part of your number is driven by biology you didn’t choose.

Knowing the factors that influence HbA1c helps set realistic expectations and supports more informed conversations with your provider.

How to lower hemoglobin A1c

Because HbA1c reflects an average over several months, meaningful change comes from routines you can stick with over time. Sustainable habits matter more than quick fixes.

Dietary strategies

- Build meals around fiber, protein, and minimally processed carbohydrates. Studies show that increasing fiber in your diet can lower both HbA1c levels and triglycerides, and increasing protein can have a similar effect on HbA1c.

- Limit refined sugars and highly processed foods, as research shows that these are linked to increased HbA1c levels.

- Pay attention to portion balance and meal regularity. One study showed that those who consumed portioned meal boxes demonstrated reduced HbA1c levels.

Exercise and physical activity

- Studies indicate that regular moderate activity can help to significantly lower HbA1c over time.

- Research shows that resistance training is an effective strategy for lowering HbA1c and will also help maintain muscle mass.

- Add light movement after meals to support glucose uptake. Studies have shown a link between high blood sugar after eating and high HbA1c levels, both of which can be lowered with even a short, 10-minute walk after eating.

Lifestyle and behavior

- Prioritize regular sleep patterns. Research shows that sleeping too much or too little can play a role in increased HbA1c levels.

- Use stress-reduction strategies that fit your routine. One study showed that high stress levels were often a predictor of high HbA1c levels.

- Keep daily schedules as consistent as possible. Studies indicate that having a set routine, particularly for meal time, can help lower HbA1c.

Medications

- Common options include metformin, GLP-1s such as semaglutide, SGLT2 inhibitors, and DPP-4 inhibitors.

- Noom’s Proactive Health Microdose GLP-1Rx Program offers easy biomarker testing along with low-dose GLP-1 therapy, if eligible, to help support steady blood sugar and sustainable habits.

How to track HbA1c progress

Tracking progress is what turns HbA1c from a one-time lab result into a useful long-term signal. Regular tracking helps you see whether changes are actually moving things in a healthier direction.

- Repeat HbA1c testing: Most clinicians recommend testing every three to six months when actively working on blood sugar stability. Annual testing is common for routine monitoring. In a more proactive approach—focused on optimizing metabolic health rather than detecting disease alone—periodic testing may also be used to understand how lifestyle changes, nutrition, movement, and stress are influencing long-term blood sugar patterns over time.

- Watch the trend, not just the number: Small shifts from one test to the next can be meaningful. Healthy habits that support a healthy A1c matter more than lowering the number.

- Pair HbA1c with other signals: Fasting glucose, post-meal readings, or continuous glucose monitoring data can help explain what is driving changes in HbA1c between lab tests.

- Track habits alongside labs: Logging sleep, movement, meals, and stress can help connect daily routines to long-term results.

- Use tools that simplify the process: Reliable at-home options like Noom’s Proactive Health Microdose GLP-1Rx Program combine biomarker testing, habit tracking, and helpful lessons from home, making it easier to follow progress consistently without frequent clinic visits.

Tracking progress over time keeps the focus on consistency and supports more informed adjustments as habits evolve.

Learn more: Inside Noom’s Proactive Health Microdose GLP-1Rx Program: Understanding the biomarkers

Signs it’s time to find out what your HbA1c is

Age, health history, and symptoms all play a role in deciding when you should pay more attention to your HbA1c levels. Consider checking in with a clinician about HbA1c testing if you:

- Are 45 or older and have not talked about testing or testing frequency

- Have prediabetes and need routine follow-up

- Have diabetes and need regular monitoring

- Are under 45 but have risk factors like:

- Higher body weight

- High blood pressure

- High cholesterol

- Low activity levels

- Having a close family history of type 2 diabetes

- Have had gestational diabetes, polycystic ovarian syndrome, heart disease, or a prior stroke

- Are experiencing symptoms associated with diabetes, such as:

- Frequent urination

- Increased thirst or hunger

- Unexplained weight loss

- Blurred vision

- Fatigue

- Slow-healing wounds

A healthcare provider can help decide whether testing makes sense for you, how often to repeat it, and what steps may be helpful based on your results.

Frequently asked questions about HbA1c and health

Many people wonder how their HbA1c numbers connect to their short-term and long-term health and what they can do about it. These answers give you the practical information you need to understand your results and work with your doctor on the best approach for your situation.

How does HbA1c relate to how long you live and the risk of heart disease or dementia?

Higher HbA1c levels have been linked to a greater risk of heart disease and cognitive decline. That can sound alarming, but there’s an important upside. Research has also shown that bringing very high HbA1c levels down is associated with meaningful benefits, including gains in life expectancy of nearly four years.

How is HbA1c measured and calculated, and is there a calculator?

HbA1c measures how much sugar has attached to red blood cells over roughly the past three months. It’s checked with a blood test, and you do not need to fast beforehand. If you want to translate your result into more familiar day-to-day blood sugar numbers, you can use the American Diabetes Association’s calculator to convert your HbA1c percentage into an estimated average glucose.

Is HbA1c only important if you have diabetes?

No. HbA1c is helpful in people without diabetes because it captures longer-term blood sugar patterns. Higher levels have been linked to increased future risk and can offer insight that a single fasting glucose test may miss. This makes it a useful tool for early monitoring and prevention.

The bottom line: HbA1c matters for current and future health

HbA1c can tell you a lot about how your body has been managing blood sugar over the past few months. And as we’ve seen, those patterns matter. They’re connected to heart health, brain aging, and how you feel now, and may even affect how long you’ll live.

The good news is that HbA1c is something you can track and influence. Small, steady changes in how you eat, move, sleep, and manage stress can shift those numbers over time. And when HbA1c improves, research shows the benefits are real: lower risk of serious health problems and potentially more healthy years ahead.

Whether you’re trying to prevent future issues or actively working to improve metabolic health, knowing your HbA1c gives you a baseline and a way to measure progress. It connects what you do day-to-day with where your health is headed long-term.

If you want to simplify that process, Noom’s Proactive Health Microdose GLP-1Rx Program combines at-home biomarker testing with habit tracking and low-dose GLP-1 support, if appropriate. It’s designed to help you stay informed and proactive about your health in a way that fits into everyday life. Get started now.

Editorial standards

At Noom, we’re committed to providing health information that’s grounded in reliable science and expert review. Our content is created with the support of qualified professionals and based on well-established research from trusted medical and scientific organizations. Learn more about the experts behind our content on our Health Expert Team page.